What is a “theme” in a work of art—and how does it shape the way we experience and enjoy it?

I recently had a conversation about this with some friends: painter and illustrator Jon Wos; writer and director Stewart Wade; and author and editor Tim White, who arranged it—thanks, Tim! It was a rich discussion—not just for artists and critics like me, but for anyone who wants to understand art more deeply, figure out why they like what they like, and discover more of it.

A theme is the unifying idea or goal of a work. It’s the end or purpose to which all—or most—other aspects of the piece serve as a means.

My favorite explanation of thematic unity comes from Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead, when the rebel architect Howard Roark says:

The purpose, the site, the material determine the shape. Nothing can be reasonable or beautiful unless it’s made by one central idea, and the idea sets every detail. A building is alive, like a man. Its integrity is to follow its own truth, its one single theme, and to serve its own single purpose. A man doesn’t borrow pieces of his body. A building doesn’t borrow hunks of its soul. Its maker gives it the soul and every wall, window and stairway to express it.

We could go deep on the meaning of “unity,” but for now, just consider that flash of irritation you feel when your favorite show gives a character a line that feels completely out of place—or when your uncle shows up to a funeral in a black suit and dirty white sneakers. Something doesn’t fit.

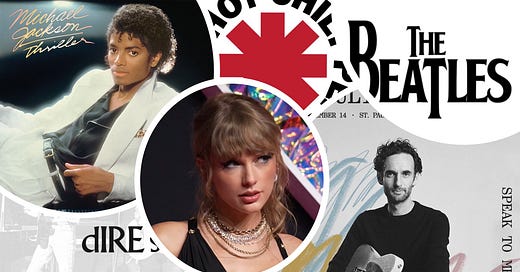

Consider a few examples of clear themes (hopefully, you’re familiar with at least one or two of these). The theme of Michelangelo’s David is that reason, skill, and mental toughness can triumph over brute force. The theme of Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus is that revenge creates a self-perpetuating cycle of bloodshed, dehumanizing both victim and avenger. The theme of Ted Lasso is that kindness and optimism can be superpowers—even in a cynical or competitive world. The theme of Mark Knopfler’s “Sweeter Than the Rain” is that justice will come for those “who live by rape and plunder.” The theme of Taylor Swift’s “You Need to Calm Down” is that people should stop wasting energy on hate and mind their own business—especially when it comes to how others live or love. And the theme of Michael Jackson’s “Man in the Mirror” is that if you want to change the world, you should start with yourself.

Of course, like your uncle’s funeral getup, not all artworks are thematically unified. And when they aren’t, it becomes difficult—or impossible—to discern their meaning, especially if the artist never clarified what he aimed to express. What’s the theme of Jackson Pollock’s Number 30 (later retitled Autumn Rhythm)? Your guess is as good as mine. What about “Eddie in the Darkness” off the latest Inhaler album? (See my discussion here. If you can convince me that song has one definite theme, I’ll give you a free “paid” subscription.) Or take almost any Red Hot Chili Peppers song—high on energy, low on coherent themes (though yes, there are exceptions).

Even so, we might still enjoy these works on other levels. This is especially true in music. Often, what we’re responding to is not thematic unity but musical unity. The music itself is unified in such a way as to express a certain mood, emotion, or “emotional atmosphere”—meaning a collection of mingled or related emotions (you could perhaps say the same of Pollock’s Number 30). “Eddie in the Darkness” conveys the hollow excitement of grasping for something or someone that is out of reach. Ian Hunter’s “F.B.I.” evokes the angst of facing an immediate threat. Julian Lage’s “Tributary” offers a thoughtful, happy calm. You probably have entire playlists filled with songs that are dissimilar in almost every respect but nonetheless share the same mood or “vibe.”

By contrast, some music doesn’t even check that box. It lacks musical unity and so doesn’t express a clear emotional atmosphere. Here’s a fun challenge: Listen to Julian Lage’s “Etude” and leave me a comment listing the cascade of emotions it evokes. Do you sense any throughline?

That’s not to say we can’t enjoy it. Just as we might enjoy a musically unified track that lacks a clear theme, we can enjoy “Etude” or the like on a more technical level—admiring the performance, the recording, or the craftsmanship (especially if we keep in mind that an étude is a study piece, meant for practicing or demonstrating a specific technique).

Still, I’d argue that we enjoy a technically impressive work even more when it’s also musically unified—and we enjoy a musically unified work even more when it’s also thematically unified.

And this last—thematic unity—is often the most powerful. Why? Because themes are fundamentally different from moods or emotions. Let’s revisit a few examples:

“Kindness and optimism can be superpowers” versus “a thoughtful, happy calm”

“Justice will come for those ‘who live by rape and plunder’” versus “angst in response to an immediate threat”

“Revenge often creates a vicious cycle of bloodshed” versus “the hollow excitement of grasping for something or someone that is out of reach”

Each pair reveals a crucial difference. The mood describes a feeling; the theme expresses a complete idea. And our ideas are more stable and self-defining than our moods. When we resonate with the vibe of a song, it says something about our current state of mind. When we resonate with a theme, it reflects something deeper—an idea we hold as true.

Moods are transient. Themes are anchored in our character and worldview. They remain fixed—unless and until we choose to change our minds.

That’s why themes have greater staying power, both personally and culturally. People have been listening to “Taxman” by the Beatles for nearly sixty years, and I’d wager they’ll still be listening to it sixty years from now—just as they’ve kept returning to Shakespeare for more than four centuries. But in five or ten years, as styles evolve, people will look for new musical expressions of “hollowed-out excitement” or “angst in response to an immediate threat.” Those moods will persist, but the packaging will change.

There’s nothing wrong with riding the wave of a musical vibe. It’s great for driving, working out, relaxing, or having drinks with friends. But if that’s all you ever do, you might be missing out on something deeper—music that reflects not only a fleeting mood, but your core beliefs.